Paul McCartney answers student questions as the ‘Linda McCartney Retrospective’ opens in Tucson, Arizona

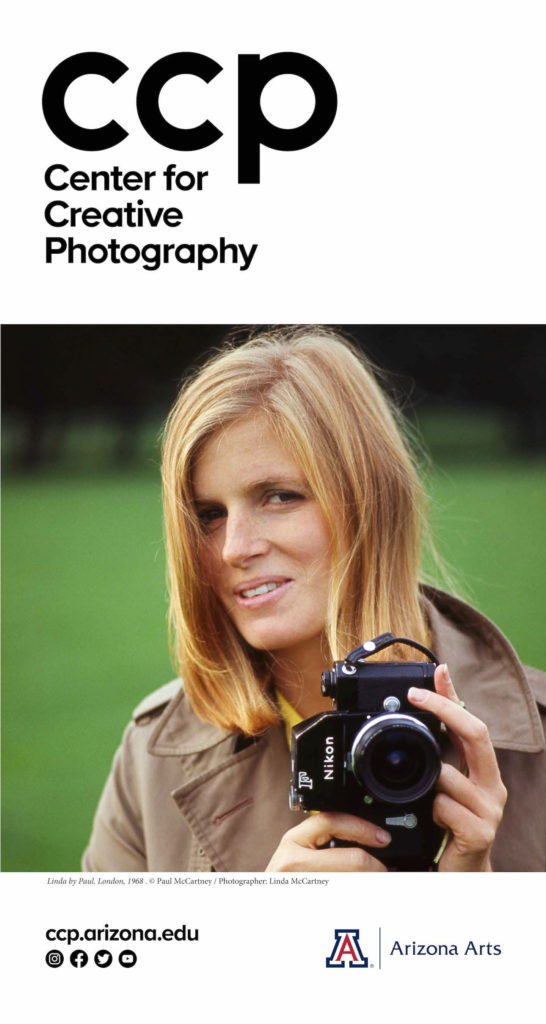

The career-spanning exhibition Linda McCartney Retrospective opens this week at the University of Arizona’s Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, Arizona – the very same university Linda attended as an art history major in the early 1960s.

Although Linda’s formal photography training amounted to just two lessons there, her tuition under the accomplished photographer Hazel Larsen Archer sparked her interest and marked the beginning of her photography journey.

Today, the university’s Center for Creative Photography is regarded one of the world’s finest academic art museums and study centres for the history of photography. It attracts students interested in examining the role photography has in society, through researching its collection of over eight million archival objects including more than 110,000 works by over 2,200 photographers. With the arrival of the Linda McCartney Retrospective, the student programme will address issues related to Linda’s work, and students will have the opportunity to engage with her photography collection through musical performances, lectures and more.

The exhibition has been curated by Paul and Mary McCartney in partnership with the CCP. To gain a further insight into Linda’s craft, students submitted questions to Paul for an exclusive Q&A session. From discussing Tucson as an inspiring location for Linda right through to describing her photography journey as a whole, Paul shares his thoughts here:

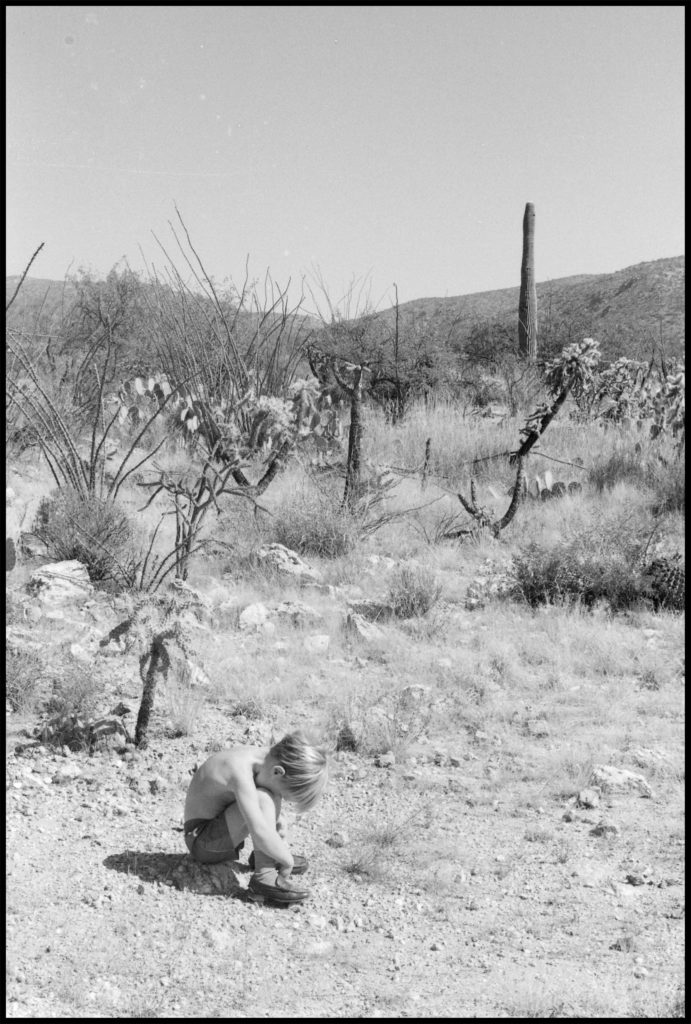

CCP students: How did Linda McCartney respond artistically to Tucson compared to other locations in the world? Did you find that she photographed with a certain camera while here, or photographed certain subjects over others?

Paul: Well, I think the fact that the Tucson location is so distinctive was very interesting to her. We both loved the desert vibe in Arizona, so I think that attracted her attention. We often travelled near the Saguaro National Park, where there were saguaro cacti everywhere and, as you can see, she loved them. Linda also loved the light of Tucson and the shadows that the light created. So yeah, it was different from other parts of the world.

The thing is, Linda was interested in taking pictures. That sounds simple but that was her motivation; if she saw a picture in life, she would want to take it.

CCP students: Do you think that the playfulness of Linda’s self-portraits reflects her own playfulness? Do you know what Linda really wanted to convey through her own self-portraits?

Paul: The thing is, Linda was interested in taking pictures. That sounds simple but that was her motivation; if she saw a picture in life, she would want to take it. So, if she was walking past a mirror she might have thought, ‘Oh, the light’s good. Let’s have a picture of this!’ I think a lot of her self-portraits came about just because of the situation and perhaps the lighting. I don’t think she ever set out to do the definitive self-portrait – they were all just moments that were captured.

When taking a self-portrait with something like a Polaroid camera, it was difficult to do successfully. Quite different to ‘selfies’ today! She would have to hold the camera at the right distance, find the button, hold the dog or whatever else was in the frame. Linda was a great photographer and loved it so much that she would always find a way.

CCP students: The Linda McCartney Retrospective exhibition is split into different themes of Linda’s work: artists, photographic exploration and so on. Which area of her photography was Linda most excited about?

Paul: I think one of the most interesting things about Linda’s photography is her journey. She started off in Tucson with Hazel Larsen Archer – she happened to go to Hazel’s class who said, ‘Get yourself a camera, take some pictures and come back next week’. So, that was the first lesson and Linda found it a lot of fun.

Then when Linda went back to New York and got involved in the music scene. She began taking pictures for music magazines like Rolling Stone and Crawdaddy. She would be at the front at a concert taking pictures of music she loved and was knowledgeable about. She once told me about the time she was taking pictures of B.B. King, whose music she adored. She felt very privileged to be in that position. Another photographer next to her was a guy who was sent along to take photos, and he asked Linda, ‘Who’s this? Who is it I’m photographing?’ And she had to tell him, ‘It’s B.B. King!’ Her love of music and photography really came together then.

After we got married, her photography started to focus on family life with the kids, horses, countryside and landscapes. Whatever situation she was in she would use it for her art, and her craft naturally developed that way. At one point she heard about cyanotypes and became really fascinated by the whole idea of printing photos herself. She loved treating the paper haphazardly and the whole process of putting it out on the balcony in the sun to develop: she thought it was magic. So, I would say she was excited about all her photography, because it was her life.

CCP students: Which artists from the 1960s had the most profound impact on Linda’s photography?

Paul: I’m not sure it was artists from the 1960s, but before that Dorothea Lange was a favourite of hers. Linda’s tastes were formed by looking at artists like Walker Evans, Ansel Adams, Georgia O’Keeffe – she was a big admirer of O’Keeffe. Growing up she knew Willem de Kooning as her dad was his lawyer, so there was a family connection.

Of course, she had studied History of Art in Tucson, although she confided in me that in those classes it was often a typically hot Tucson afternoon and they’d be in a little dark room watching a projection, so sometimes she might nod off. I imagine current students might relate to that, too!

But anyway, Linda had a pretty wide knowledge of art. That was one of the things we both had in common when we first met. I was enjoying people like Magritte, which impressed her. One of my big show-off moments was asking, ‘Have you seen my Magritte?’

CCP students: How did Linda come to photograph the musical artists of the 1960s? Did Linda find it easy or difficult interacting with such a diverse group?

Paul: It was easy for her because she loved music, therefore she knew their music. She didn’t just show up and go, ‘Oh, what kind of music do you play?’ She’d heard their music and maybe even seen them live before, whereas a lot of other people wouldn’t be interested. From an early age growing up in New York, she was in the era of the doo-wop groups. She was very knowledgeable about that. I remember her talking to Paul Simon who was also a New York kid from that era, and they knew all the little groups that we didn’t get over in the UK. Linda could hang out with Jimi Hendrix and he would be impressed that she knew who B.B. King was. That made things easier on the music scene. She knew what was going on!

CCP students: How did Linda’s parents influence her decision to pursue photography?

Paul: Her family had a love of art, and there was a lot of art in her life from a young age. Her grandpa had come over as an immigrant from Russia and he was a bit of a painter. There was this family story that her dad Lee had a picture by her grandad up on the wall and a famous art connoisseur friend of his said, ‘I’d like to buy that, who’s it by?’ And he replied, ‘It’s by my dad and it’s not for sale!’

Anyway, the point I’m making is that art was always there. Her dad was a big collector of very good art and ended up being a lawyer to quite a few artists like Robert Motherwell and Willem de Kooning, so there were always great pictures around. I think that was a big influence. Then going to college in Tucson and taking the Art History classes.

CCP students: How did Linda balance taking photos of her family while staying present in the time she spent with them?

Paul: I think raising a family and having a career is normally very difficult, but for the two of us – me being a musician and her being a photographer – we could pretty much do it anywhere. I could write songs anywhere, she could take pictures anywhere.

Linda was a really good mum and a good cook, and she put a lot of time into raising the family. We both did. I’ve got memories of me making bits of furniture out of old potato boxes, and she’d take a picture of it. She’d take Polaroids of egg cups that were cute, or she found interesting. She’d do that alongside whatever she was doing in the house or with the kids. She was able to combine two things, being a mother and a working photographer.

CCP students: Taking a deeper look into Linda’s family portraits and the beautiful moments she captured, would you mind sharing a little more about why you think she captured all these fun moments with your family?

Paul: It might sound simplistic, but if you’ve got a good photographer’s eye you will spot a good situation and a good bit of lighting anywhere. For Linda, it was often to do with the lighting, and our daughter Mary does it now as well. She’ll move you around saying, ‘The lighting’s better here,’ and she’s always right.

It was mainly just whatever was in Linda’s life that was available to be photographed. If we were outdoors in Tucson, for example, she would take a photo of the saguaro cactus, or a barrel cactus or a yucca (we got to know all the cacti quite well!). When the saguaro is in bloom it’s very beautiful, and that was all happening around us, giving Linda plenty of material for photography.

CCP students: Which photography technique did Linda use most often, and why?

Paul: Linda was fascinated by all forms of photography. She started off with a Nikon camera, and there was a technique where she would pull off a little piece of the Kodak film box and pop it into a little slot at the back of the camera to remind herself what film she was on. A clever little trick!

Linda started off with that, then she got into Polaroids. We were always a little bit worried about using Polaroids, as there was a rumour going around at the time that they wouldn’t last – which is happily not true – they have lasted! Linda loved the format, and then she got a big 10×8 plate camera and started to become fascinated with that for more formal shots. She took some great portraits of the British artists Gilbert & George using that camera, getting under the big blanket and trying it out. Really, she was interested in all forms of photography

CCP students: Linda’s work often seems based on intimate moments. Could you speak a little more about her values as a photographer, such as what she wanted to accomplish and what she found important to convey?

Paul: Linda was a very strong animal-lover, really strong – people will say, ‘Oh I love animals!’, but with her it was very deep. She had a kind of Disney-esque view of animals, so no matter what animal it was, it was ‘cute’. If it was a frog, it was a ‘cute frog’. If it was a beetle, it was a ‘cute little beetle’ – like me!

She loved animals so much. If she went past a butcher’s window and saw animals hanging there it revolted her, because to her they were cute animals that were now dead for man’s pleasure. She got pretty annoyed about that, so she photographed it. Documenting what we’d see as abuse. If it was the open back of a meat truck showing a big carcass hanging up, she would take a picture of it rather than just going, ‘Yuck!’ and walking away. Linda had this activist feeling that she wanted to show people what was going on.

This feeling went through all animals. I remember once when we were at the artist Paul Caffell’s place doing platinum prints with him. It’s a fascinating process, you see them come up and it’s magical. We were having a break in the garden when Linda saw a frog and picked it up! People were going, ‘Oh, my god! You’re picking up a frog?’ And Linda knew it might pee on her as a defence mechanism, but she didn’t care. Mary has some great pictures of her holding the frog’s arms. She could hold animals so that it didn’t hurt them, which was a bit of an art in itself. Animals were very comfortable with her and she was very comfortable with them.

CCP students: You and Linda shared a creative partnership through the music you made together and with Wings. Did this creative partnership extend to photography as well?

Paul: I was very into photography, so I could relate to what she was doing. But I knew she was better. There was never any question of that. I admired her skills, and we could talk about photography. For example, we’d talk about light settings, or lack of! She wasn’t a big light meter person. She would guess it which is quite amazing actually when you look at some of the pictures. There’s this photo of James in Scotland where he’s jumping in the air and I’m balancing on the fence, and I’m sure there’s an awful lot of technical stuff going on in that photo that I wouldn’t begin to know about. Linda had to capture James’ motion, so there’s a shutter speed involved. She had to get the distance and the foreground and background all in focus. She had a natural skill for all that.

I remember talking to Robert Fraser once about what constituted a good picture, and we ended up both saying that you’ve got to be in the right place at the right time. Then you’ve got to know when to click. Linda was very good at that. She could make people very comfortable; she was not one for those long photo sessions. Instead, she would take one or two casual shots and then put the camera away. She didn’t like a huge set-up with lots of lights and things: she wanted her subjects to be at ease.

The Linda McCartney Retrospective is at the University of Arizona’s Center for Creative Photography from 25th February to 5th August 2023 and is free to visit. For more information, head to the CCP website.